NAIDOC Week 2021: What a referendum ballot could and should look like

This week, for NAIDOC week, the Indigenous Law Centre, UNSW, and the Uluru Dialogues are very excited to bring you a special blog series. Every day this week, we will bring you a short blog from legal and political experts from across the country to answer some of the trickier questions about the constitutionally enshrined First Nations Voice to Parliament.

__

08.07.21

If and when the Australian people go to a referendum on whether to constitutionally enshrine a First Nations Voice, they will express their views on a ballot paper. For many Australians, they will never have seen a referendum ballot; for others, it will have been over 20 years.

Can design of the referendum ballot lead to a more informed and deliberative engagement of voters with the question at hand? This matters, because informed consent, not just consent, by citizens is a precondition of functioning democracy. Another good reason to think about this question is that referendums that fail to inform and engage voters are also stacked against success.

Voters face problems of low knowledge, misinformation and ‘enclave deliberation’. That is, they discuss the reform among like-minded people and therefore have little new information or arguments. This means they may know neither the ‘what’ nor the ‘why’ of reform. This can risk them voicing opposition to reforms based on underinformed and superficial reasoning.

There are a number of interventions that may support more informed and ‘deliberative’ voting. Let’s consider the design of the ballot as just one of those.

If we start with some basic principles if we were to design a ballot for constitutionally enshrining a First Nations Voice:

First, a referendum question should be succinct to aid voter comprehension. But succinct doesn’t mean there is no information; there should be a general statement about the intended nature and function of the Voice.

Second, the question should counter known misleading claims about the power or nature of the Voice, eg, the third chamber argument that has long been put to bed.

Technicalities about the precise structures of the Voice should be omitted. Voters better understand broad constitutional rationales and forms, and indeed are more open minded than many elites when reasoning about such broad principles.

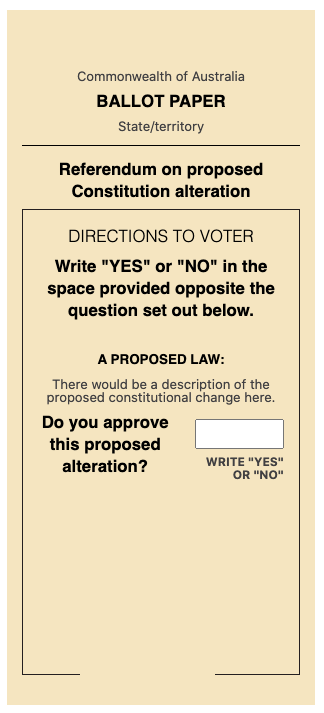

The Referendums (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 currently sets out what a referendum ballot must look like, and unfortunately, it doesn’t allow for much flexibility. It stipulates the following:

Because of these requirements, Parliament has been forced in the past to pack what information it could into the proposed law’s title. For a First Nations Voice referendum, the law could be titled so that the referendum could be:

A proposed law: To alter the Constitution to establish a First Nations Voice to guarantee Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people an institution that can provide non-binding advice to the Parliament about the development of Commonwealth laws and policies affecting them. DO YOU APPROVE THIS PROPOSED ALTERATION?

But there is no reason why the Referendums (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 can’t be amended. Section 128 of the Constitution requires that a ‘proposed law for the alteration’ of the Constitution be ‘submitted … to the electors’ (voters). Changes to the Act could allow, for instance, the ballot to include the amending law’s preamble as well as its title. This would list the law’s rationales on the ballot.

Preambles to constitutional reform bills have been successful overseas when focused on the basic and broadly agreed values. For instance, the Belfast Agreement’s ‘Declaration of Support’ relied on ‘tolerance’, ‘mutual respect’, ‘equality’, ‘partnership’, etc. Including the values that the reform represents can have ‘priming’ effects for voters. That is, it can prompt purposive deliberation, steering discussion away from divisive positions and favouring agreement.

Other information could be included about the reform in the ballot that is not part of the legislation. This could be drafted by independent experts, and approved by a statutory authority such as the electoral commission to ensure it is objective and fair. Of course, any information should remain succinct, but allowing more flexibility in information provision might increase voter comprehension compared to a long and wordy legislative title.

Ballot design could even have effects beyond the polling booth on the day of the referendum. If the contents of the ballot are publicised in advance, including on traditional and social media, the contents may rebound to earlier stages in the referendum. The ballot may set the assumptions, terms and scope of debate throughout the referendum campaign.

__

Associate Professor Ron Levy is a Senior Lecturer in law at the Australian National University.